Or Else above the Desertron

by Cass Francis

Images of atoms depict dots in orderly lines, a microscopic grid providing the form for material reality. The naked human eye cannot see atoms. In fact, our only images of atoms come from special microscopes, the scanning tunneling microscope, which wields electronic scanning and computational data to depict the miniscule building blocks of matter. Or something like that. I am no physicist, though as a child I watched a documentary that depicted atoms as little bubbles with strings within them. A trampoline-like curtain of strings rippled under the bouncing bubbles of the atoms, and the atoms became the planets and the stars of the vast and unknowable universe.

In school, we discussed atoms with the same intensity and wonder as other scientific phenomena that, come to find out, rarely factor into navigating daily adult life. Quicksand, the Bermuda triangle, the glowing translucent fish at the bottom of the Mariana Trench. We were taught about these not because every adult needed to know about the specifics of the alien features of our own world, but because we needed to learn to dream of the world beyond what we could see.

An atom consists of protons, electrons, and neutrons. We drew crayon diagrams of them, the orbital paths in shaky pencil and the elements in waxy green, blue, and red, drawn on flimsy printing paper.

In my drawings, I saw beyond the boundaries of small-town Waxahachie, Texas, my hometown, and I saw the matter deep within it. I shared within me the same bits of electricity that zapped through the black dirt under my feet and the yellow pasture grass and the wind and the cattle and my grandfather’s brick house and my grandmother’s honeysuckle and the earthy rain that fell in spring. Gazing out the fingerprint-smudged window of the backseat of my parents’ car, I would picture what we passed as the grids of atoms. The winding streets, the apartment buildings on the edge of town, the houses under construction in the new suburban neighborhoods, the bank, the McDonald’s, the movie theater, our church—all made up of those invisible orderly rows of dots.

What drew them together? How did they know what shape to take?

It all seemed so tenuous, reality. Even in the small Christian school where I learned of atoms as being in conjunction with God’s divine plan for the universe, I found myself thinking of the atoms which make up all creation the same as lego blocks. How easy it would be to rearrange the order of the world. How easy it would be to recreate the world to make its wonders less alien, more visible.

***

I am not sure whether certain memories from my childhood were real or from fever dreams. A play in which my schoolteachers at the Christian school I attended acted out falls from grace and their unique but predictable trips to hell. A preacher raging about walking naked down the street and seeing a plot of land where he decided he would build his church. Voices speaking in tongues and hands raised to sun speckled rafters and fingers pointing at the demons in our midst. One sermon was about old dogs. I remember nothing about it except the way the preacher described the dogs as old and stiff legged loping behind him with their tails tucked and their tongues dripping in the heat. I remember the preacher saying we should learn to be as faithful as those dogs in order to know the love of God.

Waxahachie is a place of comfortable morality. Life is straightforward, if not simple. The passage of time is marked by the community parades for every holiday and homecoming. Historic buildings are refurbished in the downtown square centered around a granite courthouse built, legend has it, by a spurned lover. Children ride bikes along the sidewalks, middle-aged and middle-class couples walk hand in hand through the antique stores and gingerbread houses, the women dressed in Easter colors and the men in flannel and jeans.

I have always longed to be of them, someone who knew immediately whether something was wrong or right. Growing up I heard that only certain people are called to follow God and I have always figured I was not, given how confused and eventually apathetic I become in moral debates. In the fever dream play in which my teachers were condemned to eternal damnation, I found the stories of sin more engaging and realistic than the heaven-bound ones they countered. A woman who simply did not believe in religion, a man who cursed God while in the throes of addiction, a woman who gave in to lust—straight to hell. The heaven bound simply kneeled and prayed and that was that. Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Well, to me saints were all alike and brutally predictable, while sinners seemed bursting with human uniqueness.

Waxahachie is not a place for sinners, or so I believed. To be honest, it is not even a place for the reformed. Rather, it is a town for the rare blessed individuals who do not even know the temptation of sin, the rich complexity of it. They believe it is some kind of illness that by divine intervention has passed over them to settle in the blood of poor sumbitches elsewhere. And above all they believe they can avoid this illness through the careful and predictable set of simple life choices they teach their children and they themselves were taught.

I could have been born anywhere, could have grown up anywhere. But I was born and raised in Waxahachie. And like many Texas towns, Waxahachie carries its own legacy and shapes its own legends. The stories of the place shape it just as much as the black dirt, the cracked asphalt, the granite downtown buildings.

‘How easy it would be to rearrange the order of the world. How easy it would be to recreate the world to make its wonders less alien, more visible.’

Lately, I find myself thinking of infrastructures that never were or at least never became what they were dreamed to be.

One of the reasons Waxahachie is famous, or near-famous, involves an infrastructure dream never realized. In the 1980s, American government officials and physicists began planning the construction of a supercollider in the town.

The Superconducting Super Collider was scientific ambition on a gargantuan scale, involving plans for a 53-mile track built in an underground tunnel long enough to lasso Manhattan Island. According to Scientific American, the vision of the supercollider was 20 times larger than other accelerators at the time and would have produced 5 times the energy of the Large Hadron Collider that now operates in Geneva, Switzerland. Maps of the plans for the tunnels showcase a ring circling the entire town of Waxahachie, stretching down past nearby Maypearl and across Bardwell Lake. I can almost imagine the energy rumbling below the ground there, charging the black dirt with good old fashioned American progress, curiosity, and ingenuity.

The so-called “God particle” was at the center of the supercollider’s vision. Physicist Peter Ware Higgs conceptualized the existence of such a particle, 130 times bigger than a proton and a deciding factor behind the birth of the universe. While “Higgs boson” is the more official name for the concept, “God particle” became popularized after physicist Leon Lederman called it the “Goddamn Particle” due to its elusiveness. Regarding why the “God particle” is so important, science journalist Robert Lea wrote, “It makes the existence of matter and interactions as we know them possible… Without the Higgs field, and thus without the Higgs boson, there would just be no atomic elements, no stars, and no life in this universe.”

The Superconducting Super Collider was an infrastructure of scientific research dedicated to unleashing and harnessing the divine physics of the universe, including detecting the God particle. Theories of its existence had been around since the 1960s, but the particle proved to be difficult to detect. The Superconducting Super Collider was designed to be the answer to the technological difficulties hampering the particle’s detection.

In those massive tunnels, the system would have beamed protons and ions almost at the speed of light, smashing them together in collisions so powerful they shattered, manipulated, and created the very building blocks of reality. But as things shook out, the tunnels lay silent, dark, and half built under the quiet hum of Waxahachie life.

***

For a long time, I loved my hometown. I thought I could mold myself to fit into its shape. I found a church I could tolerate and I read the Bible and I imagined myself in the future on the arm of a clean-cut guy who watched football and went fishing. We would get married and take out a mortgage on one of the historic gingerbread homes and we would fill it with antique furniture surrounding a massive flat-screen TV. We would have my parents over for dinner. We would pray before eating. We would laugh at Facebook memes. We would shake our heads in sadness and sympathy for all those who could not be as wonderfully normal as us.

On weekends, I would often accompany my grandparents to yard sales. My grandmother would navigate from the front passenger’s seat, Mapsco book pages diagraming the town’s streets spread across her lap. We pawed through the belongings of people all across town. Toy trucks with missing wheels and dolls with stuffing poking from frayed stitching. Spine-cracked books and faded DVD boxes hot and half-melted in the sun. Piles of clothes that smelled of strangers. Sometimes, the people would watch us from the safety of whatever shady spot they had found to perch and collect their cash. Other times, someone would come trailing after us, interested in whatever we picked up, ready to tell its story. Got that at a flea market, they would say. Got that at a bookstore in Houston. Got that back when I lived in Dallas.

Sometimes I would buy something just because I wanted its story. Once, I picked up a wooden cane, painted black with a hook at the top and a rubber tip on the bottom. I was interested in it because of a nerdy obsession with Charlie Chaplin. The man selling it said tearfully that it had been his mothers. My mother’s favorite cane, he had said.

The stories we tell about things shape them. Yes, the atoms of material reality pull together through some secret force but they buzz with the electricity of the stories we tell of them, the stories we share with them.

On the way to one yard sale, my grandmother, who was also from Waxahachie, said that growing up the locals had called this part of town Ignorant Hill. The hills were not dramatic in the prairieland of the town, but this neighborhood did slope upwards slightly. The roads became narrower, cars passing one another with tight apprehension. One small swerve and a side mirror would have been banged off by a passing car. The houses became small and crumpled, leaning in cramped and overgrown lots. It did not take a historian to tell me that Black, Hispanic, and poor people had occupied these houses, and probably occupied them still.

I began noticing the benign cruelty at the core of my hometown, disguised as a natural politeness and a desire to not rock the boat. And the cruelty carried on because it was whispered, designed right into the infrastructure of the town and only spoken in hushed and apologetic tones, as if the unfairness of it was physical and therefore natural and unchangeable. The atoms had already found their form and we could not question them.

This was a strange philosophy for a town that had once dreamed of smashing protons together until the very element that created the universe appeared. I began to wonder about Waxahachie and my place within it. The doubting of your hometown that often appears in late adolescence. The gradual dawning on you that the worldview carefully constructed around you is a false one. That the ground you stand on may be hollow.

Eventually nicknamed “Desertron,” despite not actually residing in the desert, the Superconducting Super Collider found its speculative home in Waxahachie due to the geology of the region. As reported in Texas Monthly, Waxahachie is “rolling prairieland” of malleable but rigid earth perfect for building the vast tunnel system. It is strange reading about the town from an outsider’s point of view, the people there depicted as friendly and faceless farmers in a community quaint and idyllic and anachronistic. In the article, the saga of the supercollider seems more appropriate for the mythic American 1950s. Scientists filled with mad but good-hearted ambition partnering with common-man families dreaming of utopian futures for their children and grandchildren, their story set among pastures of yellow grass rippling in the wind and wide open blue skies.

When not dreaming about being the perfect Christian housewife, I dreamed of being a farmer. No matter that I am extremely lazy and hate early mornings—I pictured myself rising before dawn with not even the help of an alarm clock, going out to the barn and feeding the horses and goats as the sun rose orange on the horizon. After all, my ancestors were farmers, or sharecroppers, anyway. The land was in our blood.

The Texas part of the Superconducting Super Collider project began in 1989. A 508-page Department of Energy report from December 1990 details the vision for the project. “The basic purpose of the SSC is to gain a better understanding of the fundamental structure of matter,” the report reads.

I think of childish crayon drawings of diagrams of atoms. It is funny how we humans, supposedly smart humans no less, try to rediscover what we already know. We try to find new ways to articulate what has always been there.

In October 1993, Congress voted to end the Superconducting Super Collider initiative. About $2 billion had already been spent on constructing the vast tunnel system. A retrospective report from 1994—the year I was born in Waxahachie—notes that staff of the lab were “shocked” by the decision, given the amount of money already spent and progress already made. The preface to the report describes the desire to document the five years of work on the project in Texas. “It was quite difficult to assemble this summary information,” the report reads with sudden vulnerability, “since many members of the Laboratory staff were in the process of coping with an unanticipated career change and the myriad demands both personal and professional that such a change presents.”

Physicist and science historian Michael Riordan noted in a 2016 Physics Today article that many reasons contributed to the Superconducting Super Collider’s cancellation. Cost estimates for the project had risen in the years since construction began, and the fall of the Soviet Union led to less of a need for America to assert its scientific and technological prowess. “A bridge too far,” one leading physicist in the community described the project. Riordan argues that its vision was too big, unwieldy, and expensive for the US to pursue alone. Members of Congress who fought to cancel the project called it “luxury science,” a costly endeavor for nothing more than status.

***

Gradually through the years of growing up, I fell out of love with Waxahachie even while remaining tethered to it. I moved out of state and yet came back home to see family every Thanksgiving, Christmas, and often during the summer.

Every time I returned I was shocked by the small changes. A new hardware store out by the old highway. The exponential multiplying of coffee shops. A new football stadium, a new high school, a new city hall, all worth millions of dollars and all quickly outgrown. In a span of twenty or so years, within my lifetime, the town’s population more than doubled, a growth spurt reflected in the cramped streets poorly designed for the bustle.

But I was more shocked by the large ways that the town had not changed at all. When many of the surrounding areas, quickly growing due to the proximity to the Dallas-Fort Worth area, separated their high schools, Waxahachie stubbornly remained as one. Just as stubbornly, despite repeated flare ups of backlash, Waxahachie kept the Indians mascot for all their sports teams. After leaving the Christian school of my childhood for the town’s public schools, I myself had worn “Lady Indians” proudly displayed in forest green script across my chest when playing high school softball, and even then petitions circulated about changing the name.

The breaking point, for me, came through a dark story right out of a Cormac McCarthy novel that unfolded in the town, at the local university right across the street from where my family lived. In 2018, an undergraduate student and softball player at Southwestern Assemblies of God University gave birth in her dormitory. The university is an extremely conservative one—I had heard of students being disciplined harshly just for watching R-rated movies. Frightened for her future, the student had told no one of her pregnancy and, after the lonely and bloody birth, disposed of the newborn girl in a nearby dumpster. The newborn did not survive, and in 2019 the mother pled guilty to manslaughter and abuse of a corpse. The Ellis County and District Attorney called the actions, “horrific and inhumane.” The mother was about my age, and many of my softball friends knew her. The story left me sickened—the lack of acknowledgment that policies in the town, county, and state of Texas and at the university led to the death of a newborn and the ruining of a young woman’s life. The legacy of secrecy and shame. The news stories and public conversation that wholly blamed the mother.

Then, I attributed the failure of the Superconducting Super Collider to the secret rot at the core of Waxahachie. This attribution in itself betrayed my origins in that very town, where no sin went unpunished and no bad turn of fate went un-moralized. Family drunks became lessons on the need to have a spouse and children to avoid loneliness. Rehab centers offered the opportunity to preach about the need to listen to your parents. People experiencing homelessness became sermons about listening to God’s call for your life. Once, a middle grader at my school had a seizure—why you should never turn to illegal drugs and must instead treat your body as a temple, everyone whispered.

“Or else,” the sermons of the community could be concluded. Or else, your life would end in ruin. Or else, your days will be marked by constant suffering.

Or else, the atoms of your carefully organized worldview will shatter, leaving you at the very edge of what is known, of what has been predicted.

‘It is funny how we humans, supposedly smart humans no less, try to rediscover what we already know. We try to find new ways to articulate what has always been there.’

After the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider, the local chemical company Magnablend bought the facilities. In 2011, a chemical plant owned by Magnablend exploded, and Waxahachie was in the national news again. I was a junior in high school at the time. “Holy shit, we’re on CNN!” I remember one of my classmates saying during a computer lab period. We were told to shelter in place and could not leave the school. The pictures on CNN’s website showed the Magnablend factory we had all driven by routinely now a ball of orange flames that consumed the firetrucks attempting to contain it. A black plume of smoke rose against the cloudless blue sky. For weeks after the fire finally burned out, the town smelled of sulfur.

And in 2012, the Higgs boson was finally detected via the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva. The Large Hadron Collider is 17 miles long and is the world’s most advanced particle accelerator. While its size and scope seem quaint next to the lofty dreams of the Superconducting Super Collider, planned to be 53 miles long, the Large Hadron Collider succeeded in pushing forward advancements in the field of physics.

Again, I find myself thinking of infrastructures that never were or at least never became what they were dreamed to be. I can’t help but feel that the abandonment of the project represents something larger. Yes, I have a tendency to conflate random events into a larger symbolism that makes sense of our confusing and complicated world. Yes, this tendency is problematic and can be downright annoying in my real life. But I see the connections clearly—the failure of a ridiculous yet noble ambition to recreate the very material of creation, in a town dedicated to maintaining order within itself.

A good twenty or so years after the cancellation of the Superconducting Super Collider, I found myself grown and far from Waxahachie, Texas, sitting in the expansive hallways of the Gaylord National Resort in National Harbor, Maryland. I was there for a scholarly conference to show off academic egos and get away from college campuses for a bit. Still smarting from being charged $20 for a single Dos Equis in the nearby neighborhood, I ferreted out a group of self-described “conflict scholars,” one of whom had brought along several bottles of hard cider he had brewed himself and was happy to have people sample.

The price for the alcohol was smalltalk. We went around telling everyone where we worked. One man said he worked at a small university in Dallas. “But I live in Waxahachie, about thirty minutes south,” he said. For a moment I was speechless. He had even pronounced the town correctly, “Wah-cks” for the beginning instead of “Wax.”

I told him I grew up there. He said he and his husband had moved there ten or fifteen years ago. I asked him how that had worked out.

He described a tension at first when they had moved there, but gradually an acceptance. He said he hangs up pride flags and hosts successful block parties in the neighborhood. We talked about the horrible traffic, the town’s horrible Walmart, the horrible parking at HEB, the only grocery store alternative to Walmart.

“But we love it,” he said. “It’s home.”

I don’t know if he knows anything about the Superconducting Super Collider, the half-constructed tunnels circling the town. To avoid sounding stuffy, especially after multiple days listening to a hotel full of academics, I did not bring it up.

I found it amazing, though, how we must have overlapped in experience of the same town for over a decade, yet had never met and seemed to have experienced a very different place there. He knew nothing of fever dream sermons or racist nicknames for discriminatory infrastructure projects or the newborn girl left in a dumpster by a frightened undergraduate. He had never heard the way scandals were whispered, in the assured tone of “or else.” Or maybe he had—I do not know. The details of our town overlap but the meaning of them does not. And then we met hundreds of miles away, all because of overpriced beer and samples of homemade hard cider and my need to dull the praterings of academics through cheap alcohol. Which is much easier to come by in Texas, I might add. Unless it’s a Sunday.

The stories we tell about things shape them. The fever dream sermons and yard sales under a hot summer sun. The atoms of reality so tenaciously held together by someone lost amid their tangled connections. I guess I learned how to love above the Desertron, in my own flawed and speculative way. A relationship with a hometown must be a bit like a relationship with anything, in that you have to recreate it according to its loveable parts and choose to believe in them, in the reality they represent. Love isn’t something to be followed, as the pastor preaching about dogs had sermonized, but something to be recreated. You’re always reimagining what it means to be home, and how the place you are could fit your imagination. Waxahachie remains my hometown, “a place in the heart,” as the town’s slogan goes. And I love it only because it is what I am left with when I remember myself and what could have been, what could still be, with a stubborn ambition to make sense of the universe.

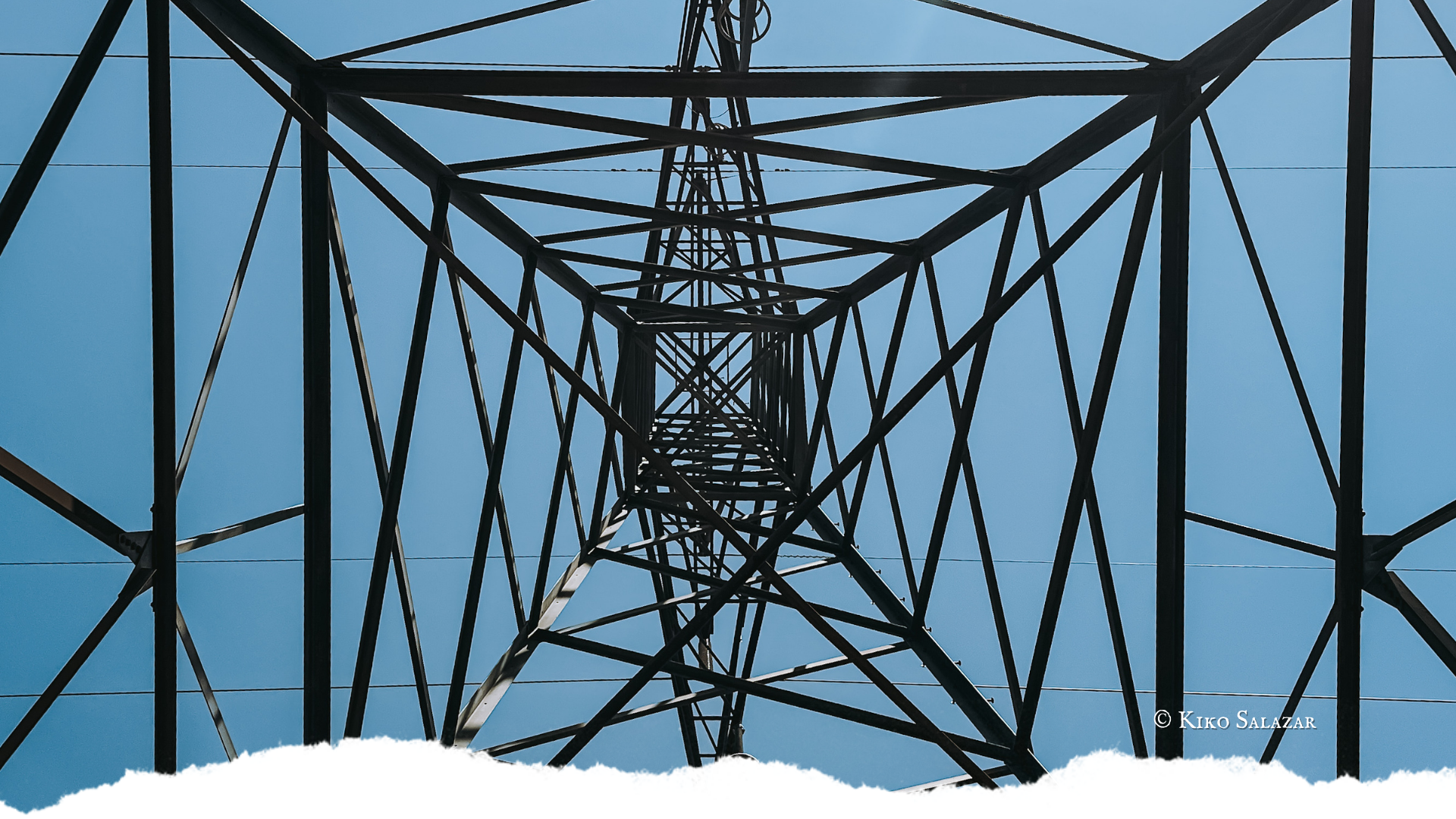

The most common image of the Superconducting Super Collider showcases a distorted view within a concrete tunnel. Two miniscule men in hard hats discuss something within the shadowy depths of the hollowed-out earth. Above them, the Texas sky can be barely seen through a hole in the tunnel. A blinding beam of light shines down. Heavenly light, almost, among the darkness along the edges of the frame.

Cass Francis is a born and raised Texan who has lived everywhere from the plains of Lubbock to the piney woods of Nacogdoches. She currently lives in the “funkytown" of Fort Worth. Her work appears in The Headlight Review, Museum of Americana, and elsewhere. Find her inactive but alive on Twitter/X.